"Retracing Anti-Asian Sentiment" by Ashley Jo

From being blamed for the spread of the “Chinese virus” to being yelled at to “go back to where you came from,” the outbreak of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has divided the world on the basis of racist thinking and discrimination. A 2020 study from California State University, San Bernardino found that although hate crimes in America have decreased by 7%, those specifically targeting Asians have increased by 150%. This rise can be particularly seen in large American cities such as New York City and Los Angeles, but as seen on the news, racial attacks are not limited to these locations. Just as the idea of “stranger danger” is drilled into the minds of children from a young age, Asians are now forced to accept the “normal” fear of being racially targeted simply because of their skin color. Though it may be easy to believe everything will pass as COVID-19 becomes less of a threat, anti-Asian sentiment is not new to America, as it has been a part of a hidden section of American history that many do not know about.

When people think of racially discriminated ethnic groups in America, Blacks and their inhumane treatment under slavery is commonly thought of. However, following the Civil War -- a fight for the emancipation of slaves -- the mistreatment of Asians also intensified. The Chinese were the first Asians to immigrate to the United States starting in the 1850s due to the growing appeal of “striking it rich” during the era of the Gold Rush. Growth in Chinese immigrants increased competition for work, angering white Americans and leading to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882. This was the first law that limited immigration against a certain ethnic group in American history. This was not America’s first attempt to restrict Chinese immigration though, as seen two years prior in the 1880 Angel Treaty signed under President Rutherford B. Hayes. Difficulty in finding enough work to support their families drove many Chinese immigrants to take on jobs of all kinds, including prostitution. This was the beginning of the Asian hooker stereotype that fetishizes Asian women, depicting them to be “easy” and sexually “desperate” with their broken English. Improved treatment of Chinese immigrants was not seen until World War II in the interest of aiding the Ally Powers, but it was short-lived as the subsequent Cold War put great economic and diplomatic strain on the relationship between China and the United States.

A second group of Asians, the Japanese, was introduced to racism in America during World War II. On December 7, 1941, Japanese forces bombed Pearl Harbor in a planned surprise attack that took the lives of more than 2,400 Americans and wounded another 1,000. Aside from the physical effects it left, the bombing also created intense and widespread fear that the Japanese living in the United States at the time were spies, prompting President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 9066 in February 1942. Under this order, “all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast [were evacuated] to relocation centers further inland,” which became known as internment camps (National Archives). Canada and Mexico soon followed Roosevelt. As a result, across the Western Hemisphere, more than 120,000 Japanese -- young and old -- were relocated to these temporary “assembly centers” that resembled army-style barracks with no protection from the heat or cold, little privacy, dirty floors, and more horrible conditions. After three years, a Supreme Court decision in Endo v. the United States brought an end to internment camps, but the psychological effects of living in the camps left permanent marks on the Japanese, especially in their family life. The loss of their homes, careers, livelihood, and identity made it difficult for them to return to “normal life”.

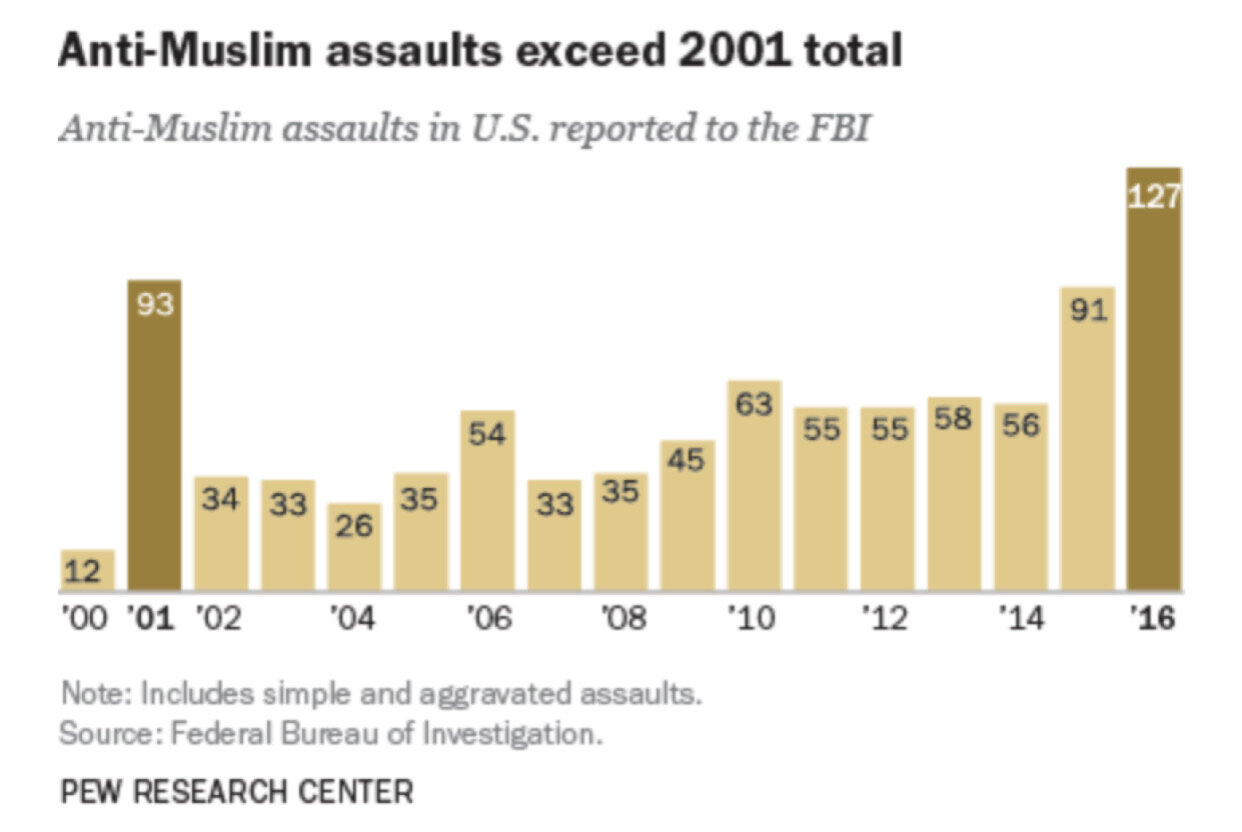

As the events following the bombing of Pearl Harbor shows, traumatic events tend to lead to discrimination against certain social and/or ethnic groups. 9/11 was no exception to this pattern, despite occurring more recently. 20 years ago, on September 11, 2001, the Islamic extremist and Salafist jihadist group “Al-Qaeda” hijacked and crashed two airplanes into the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center in what was described as the “worst and most audacious terror attack in American history,” according to The New York Times. The attack left about 3,000 dead and more than 6,000 injured, but its devastation was not limited to only that day. According to the Pew Research Center, in contrast to the 12 reported anti-Muslim assaults in 2000, the United States saw an increase in assaults the year of 9/11 with a total of 93 attacks. Though these occurrences decreased in the following years, 2016 surpassed the previous peak with a total of 127 assaults. Other forms of hate crime, such as intimidation and destruction of property, have also increased as 75% of Muslim American adults in 2017 reported noticing a spike in discrimination against Muslims in the United States. This heavily affected Asians due to the large majority of Muslims residing in the Asia-Pacific region, found by the Pew Research Center in 2010, with many Muslims being labeled as “terrorists” and “dirty.” Discrimination against Muslims was taken a step further through former President Donald Trump’s Muslim Travel Ban in 2017, which current President Joe Biden reversed in 2021.

Occurring even earlier than the events of 9/11, the term “Hallyu wave” is commonly used to reference the exponential growth of Korean culture and popular culture from music, entertainment, cuisine, and more. Though the exact time in which this wave began is unclear, many credit the musical group Wonder Girls for expanding the global audience of Korean pop (K-pop) back in 2009 when they first cracked the Billboard Hot 100 chart with their hit song “Nobody,” according to Vox. Many groups have been able to follow their predecessor; however, despite the immense popularity K-pop has gained, there has also been great backlash, specifically in regards to one of the biggest boy groups in the music industry, BTS. After the release of the group’s cover of “Fix You” by Coldplay in February 2021, a host on a German radio station described them as “some crappy virus that hopefully there will be a vaccine for soon as well” in addition to stating BTS “will be vacationing in North Korea for the next 20 years” (Firstpost). Although the Bavarian radio station came out to apologize on behalf of their host’s comments, it is blatantly clear that the world is still far from abolishing racism completely. Additionally, BTS’s recent loss at the 63rd GRAMMY Awards for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance for their Billboard #1 song “Dynamite” has been questioned to be motivated by racism. The Recording Academy has not formally addressed this issue. Few days after the Grammys, Topps Company released a Grammy-themed Garbage Pail Kids cartoon series, including the boy group, but received extreme backlash for the image to be “racist amid the rise in anti-Asian violence across the country” (USA Today). The company released a formal apology on Twitter on March 17, 2021, apologizing and removing the sticker card from the set.

Anti-Asian sentiment has been repeatedly seen throughout history, in both extreme cases as highlighted earlier in this article and more common cases in day-to-day life. With the growing popularity of Asian culture through K-pop, Anime, boba, stationary, and other aspects, it may seem like the globe is making positive progress in becoming a more racially accepting world, but that cannot be further from the truth. Asia is not limited to only East Asia; there is South/Southeast Asia, Middle/Central Asia, Indigenous/Pacific Island Peoples, and more. As AAPI month is being celebrated and the world continues to fight against Asian-targetted hate crimes, let us find strength in remembering what Asians have had to endure in American history. Let us conquer the current issue at hand together.

For further enrichment, check out Today’s Anti-Asian violence: The History of anti-Asian racism in the US.

Sources:https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/anti-asian-hate-crimes-increased-nearly-150-2020-mostly-n-n1260264https://history.state.gov/milestones/1866-1898/chinese-immigrationhttps://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/pearl-harbor#section_5https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/?dod-date=219#:~:text=Executive%20Order%209066%2C%20February%2019%2C%201942&text=Issued%20by%20President%20Franklin%20Roosevelt,to%20relocation%20centers%20further%20inlandhttps://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocationhttps://www.today.com/news/anti-asian-violence-history-anti-asian-racism-us-t210645https://www.businessinsider.com/what-happened-on-911-why-2016-9https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/15/assaults-against-muslims-in-u-s-surpass-2001-level/https://www.chicagoreporter.com/blatant-racism-against-muslims-is-still-with-us/https://www.vox.com/culture/2018/2/16/16915672/what-is-kpop-history-explainedhttps://www.firstpost.com/entertainment/german-radio-station-issues-apology-after-twitter-calls-out-racist-remarks-on-bts-fix-you-cover-9353961.htmlhttps://www.usatoday.com/story/entertainment/celebrities/2021/03/17/bts-fans-criticize-topps-sticker-portraying-band-bruised-faces/4734929001/